An advanced AI system trained on thousands of fossil footprints has re‑identified several 200‑million‑year‑old tracks as belonging to early birds, potentially moving the origin of avian flight back by 60 million years. The model quantifies subtle shape and pressure patterns, delivering high‑confidence classifications that challenge traditional dinosaur‑centric interpretations of Late Triassic trace fossils.

How the Deep‑Learning Model Works

The research team built a deep‑learning algorithm that ingested a dataset of nearly 2,000 verified fossil footprints and millions of synthetic variations mimicking wear, substrate differences, and preservation artefacts. By training on this extensive library, the AI learned to recognize diagnostic patterns that are difficult for the human eye to detect.

Feature Extraction and Probability Scoring

The system distills each footprint into eight key diagnostic features, including:

- Overall contact area

- Toe spread

- Heel position

- Pressure distribution across the foot

- Hallux (rear toe) presence

- Footprint curvature

- Depth variation

- Substrate imprint consistency

Each feature contributes to a probability score that ranks the likelihood of the track‑maker being a non‑avian theropod, a basal dinosaur, or a true bird. In validation tests, the AI’s classifications matched expert assessments about 90 percent of the time.

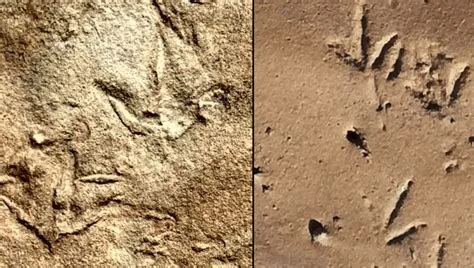

Key Findings from Late Triassic Tracks

Applying the model to a collection of Late Triassic footprints from the Karoo Basin (South Africa) and the Newark Supergroup (North America) revealed eight specimens that align closely with the avian signature. These tracks display a narrow, three‑toed imprint, a pronounced hallux, and a balanced weight distribution—traits typical of modern bird footprints.

Implications for Avian Evolution Timeline

If these re‑identified tracks indeed belong to birds, the timeline for the evolution of powered flight would shift dramatically. An avian presence in the Late Triassic suggests that critical flight adaptations—such as a keeled sternum, modified forelimbs, and advanced feather structures—emerged at least 60 million years earlier than previously documented. This revision could reshape hypotheses about the ecological pressures that drove the origin of flight.

Caveats and Future Research Directions

While the AI provides a high‑confidence hypothesis, it does not constitute definitive proof. The authors emphasize the need for corroborating evidence, such as associated body fossils or detailed sedimentary context. Future work will expand the training dataset, refine sensitivity to substrate effects, and integrate AI outputs with traditional paleontological expertise to validate controversial trace fossils worldwide.

Conclusion: A New Frontier in Paleontology

The AI model’s reclassification of 200‑million‑year‑old footprints as avian marks a potential paradigm shift in our understanding of when birds first took to the skies. By marrying deep‑learning techniques with classic ichnology, researchers open a new frontier for uncovering hidden chapters of Earth’s deep past—one footprint at a time.